Announcing Onehouse LakeBase™: database speeds finally on the lakehouse

TL;DR

Introduction

There’s a phrase I’ve heard repeatedly over the last two years, usually said with a straight face and a quiet sense of resignation:

“The lakehouse is our source of truth… but we serve data from something else.”

That “something else” is rarely just one thing. It’s a warehouse. It’s ClickHouse. It’s Pinot. It’s Druid. It’s Elasticsearch. It’s MySQL. It’s a bespoke materialized-view service. It’s a fleet of Postgres replicas held together with hope and cron jobs. And the common connection is just the disappointment that this is needed. Despite the promise, the lakehouse never fully became a database.

In 2025, that gap stopped being tolerable. Not because humans suddenly demanded millisecond queries on petabytes. Humans have always wanted that, but they learned to live with seconds to minutes. The gap became intolerable because machines don’t wait.

AI agents don’t “run a query” and take a coffee break. They think by querying. They generate high-cardinality filters, point lookups, correlated subqueries, and rapid iterative exploration as part of a tight reasoning loop. They fan out across tools. They retry. They refine. They parallelize. They do it all again. And they do it at a pace that turns today’s lakehouse query engines—and worse, your operational databases—into collateral damage.

Today we’re announcing Onehouse LakeBase: a database-speed serving layer built directly on open lakehouse tables.

LakeBase serves ultra low-latency SQL workloads directly from Apache Hudi and Apache Iceberg tables through a Postgres-compatible endpoint, without forcing you to copy data into warehouses or specialized serving systems. This post is technical, because we need senior engineers who have been burned by these ducktaped architectures, to lean in, recognize the problems we are about to discuss, and guide their teams to safety.

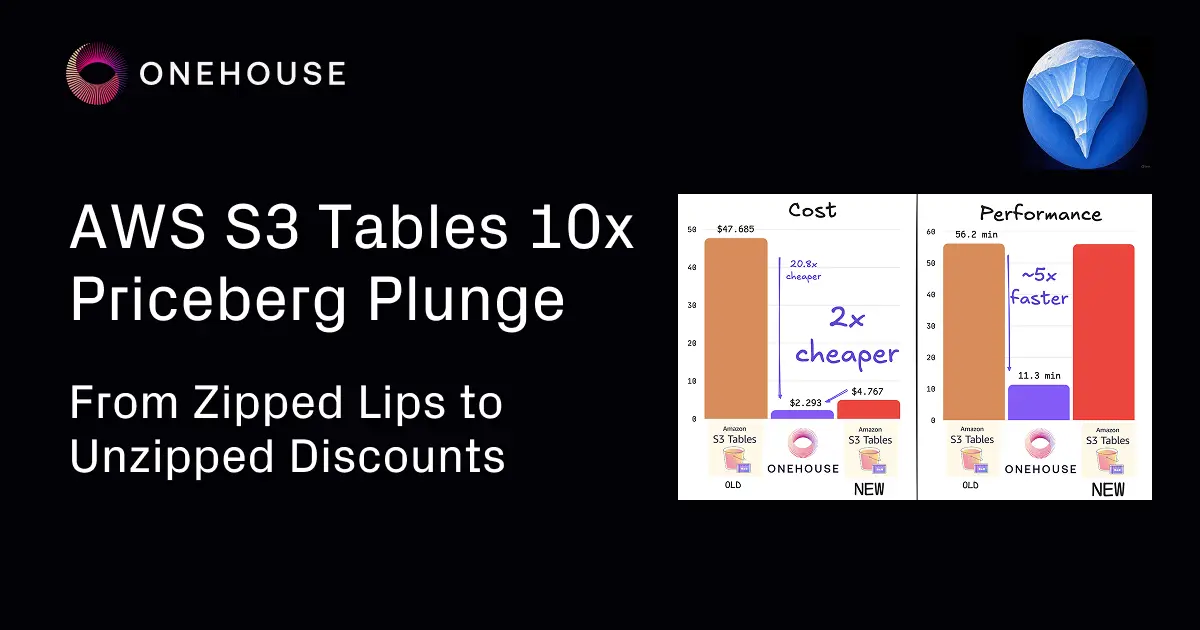

(1) The lakehouse got us far — but not all the way

2025 was a defining year for Onehouse. We’ve pushed hard on the foundational pieces of the open lakehouse: ingestion, table services, compute runtime and the Quanton query engine. If you want the highlights (and links to the deeper posts), start with our year-in-review recap. At this point, Onehouse is the lakehouse-as-a-service that is most open (all formats, all catalogs), most flexible (plug-and-play BYOC deployment) and cost-effective (see our Spark/SQL benchmarks). But, there was still a huge problem we had not addressed, that suddenly became critical in 2025.

The lakehouse is excellent at scans, but it is not built for serving.

That statement is not a knock on Spark, Trino, Presto, or Athena. They are phenomenal systems, for what they were designed to do. But the architectural center of gravity for most lakehouse engines is a distributed analytical job that can afford seconds of planning and scheduling overhead, and whose performance envelope is optimized for throughput and cost. That’s why, even a couple years ago, when we previewed Hudi 1.0, we framed the goal explicitly as a database experience on the data lake—not just better ETL, but interactive access patterns: indexing, point lookups, and fast incremental reads. The reason that vision didn’t immediately dominate was that the workaround was “good enough”: if latency mattered, you served from a different system. You paid the cost in duplication and operational complexity, but you shipped.

AI agents changed the cost curve. They turned “serving” from a feature into a survival requirement.

(2) Why now? AI agents changed the shape and scale of access

Before agents, most organizations made an implicit bargain. They accepted that the lakehouse was where data lived, but not where latency-sensitive queries ran. When latency mattered, the default playbook was:

- copy curated data into a warehouse,

- or stream subsets into a specialized system,

- or punch holes into operational databases (and hope someone wrote guardrails).

This was painful, but manageable, because the demand profile was human. Humans generate spiky, low-concurrency workloads: an analyst runs a query, waits, reads a chart, thinks, then runs another query. That gives data infrastructure time to breathe. Dashboards were static, easily cache-able to handle “thundering herd” problems, where many users open the same dashboard within a company.

Agents don’t behave like that. They are personalized for a specific task and even for a particular user. Agents build an internal plan and then execute it through tools. If one tool is “SQL,” the agent will call it repeatedly as it refines hypotheses. Tool-calling agents are now a standard architecture pattern across vendors: you have an orchestration loop that issues multiple SQL calls, joins results, and iterates.

How do agents struggle to get some context?

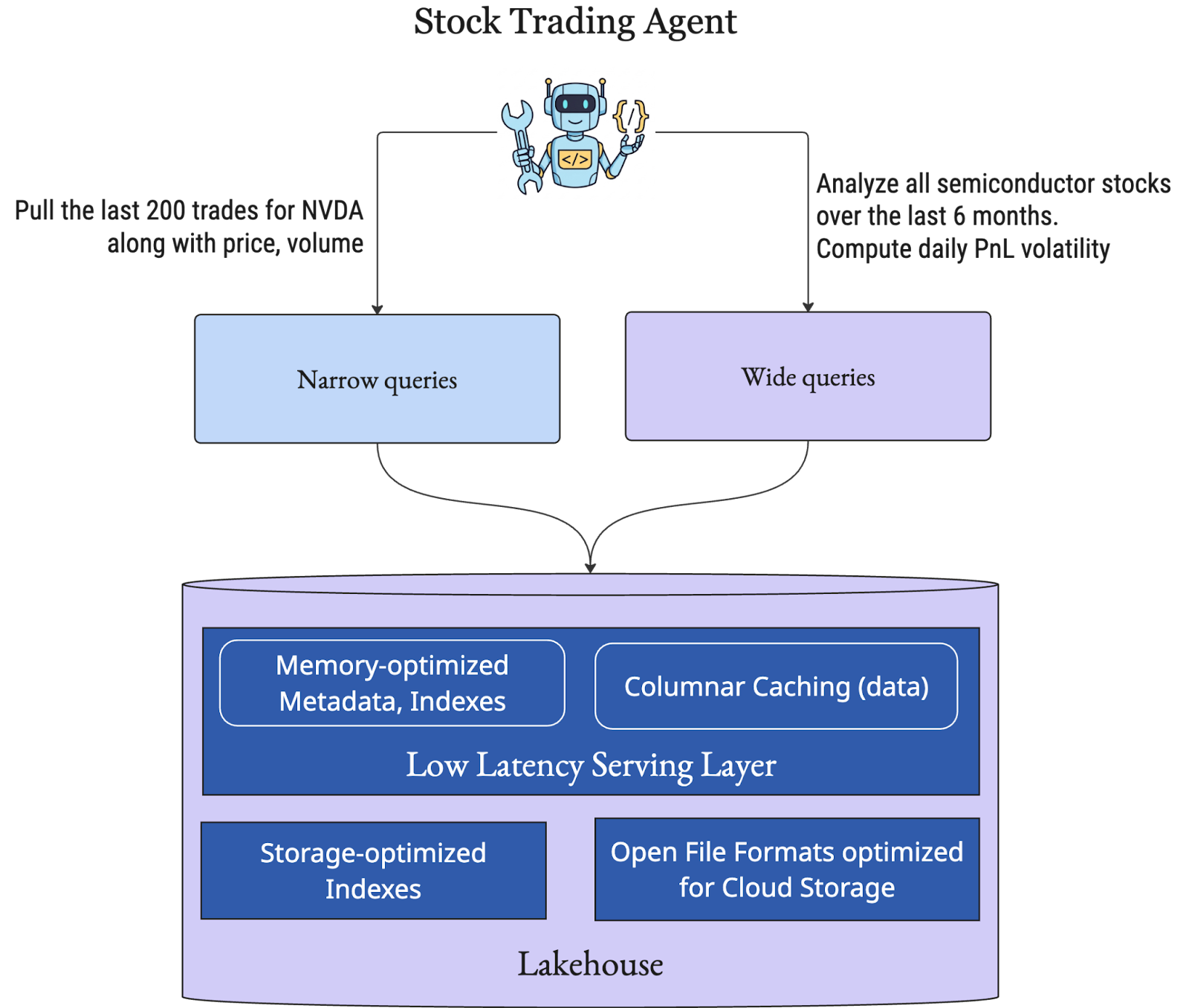

Put yourself in the shoes of the AI engineer wiring SQL tools into a trading agent. The agent is asked: “Analyze our semiconductor exposure and explain recent NVDA volatility.”

Internally, the reasoning loop looks something like:

- Identify candidate stock symbols (wide scan over that sector)

- Compute historical volatility metrics (aggregation over time windows)

- For top outliers, fetch recent trading activity (narrow lookups)

- Co-relate with other signals market sector, trading desk (join against dimensions)

- Refine hypothesis and repeat, upon next prompt

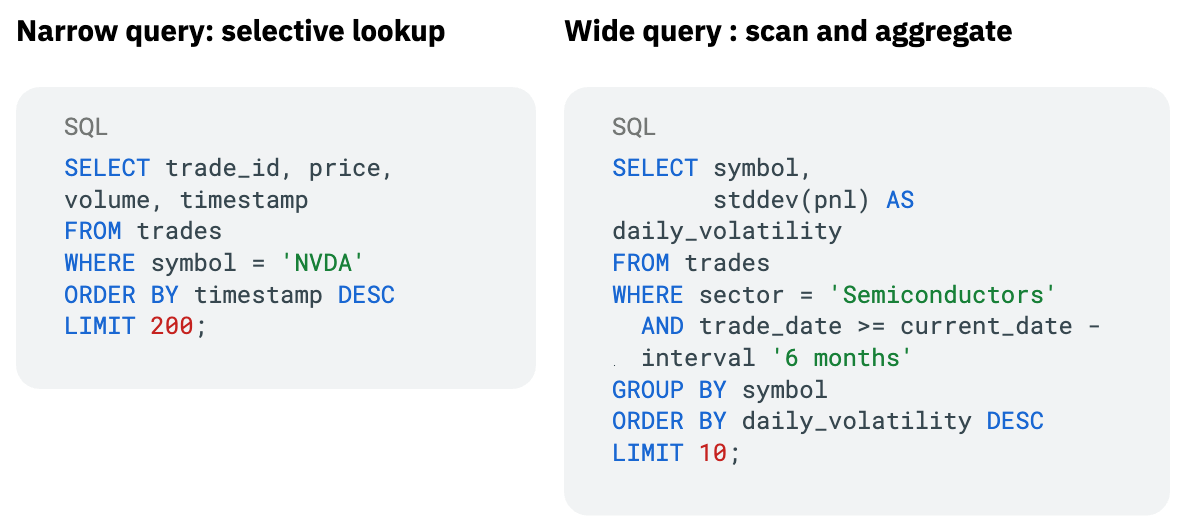

Concretely, the agent does these SQL commands:

The same reasoning loop may then perform indexed joins back into large fact tables, repeatedly. These queries are interleaved, iterative, and often parallelized across multiple candidate symbols inside a single agent execution graph. This can quickly rack up a lot of different query shapes at high qps. A slow query stalls the entire agent step and if you are deploying your own models, GPUs could sit idle waiting on tool responses.

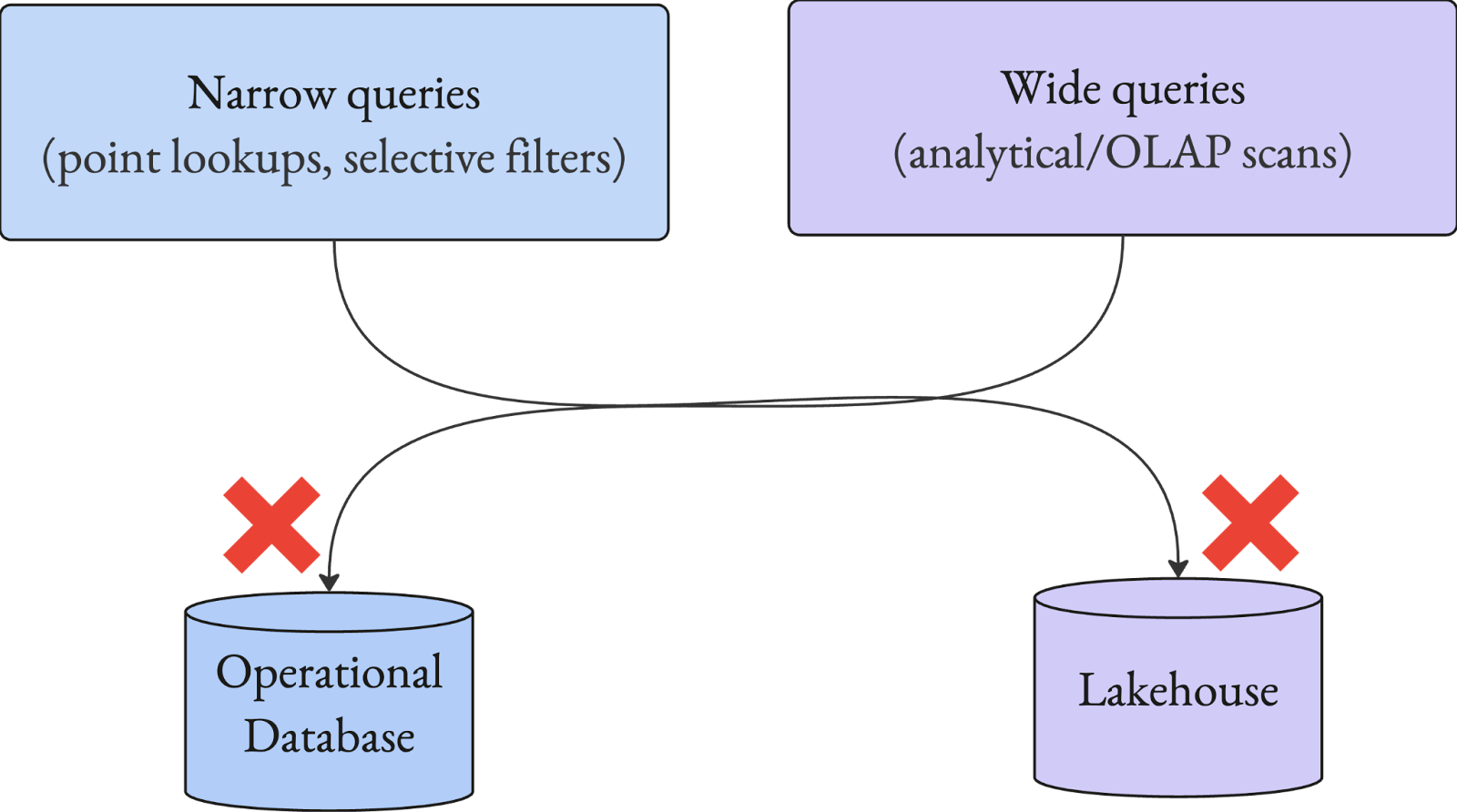

Now layer this onto what a sensible architecture looked like 2025: Agents query something like Postgres or a lakehouse/warehouse; In practice, agent-driven workloads create two failure modes simultaneously:

(a) Narrow queries like point lookups and high-cardinality filters—on systems built for scans

This is the “needle-in-haystack” pattern. The question looks innocent:

“Pull the last 50 events for user X, then filter down to the subset with property Y, then enrich with dimension Z.”

Operational databases are built for this. An index narrows the candidate set quickly. Memory caches and buffer managers do what they were born to do. Latency stays tight. A lakehouse engine often treats the same question as a planning + scan problem. Even if file pruning eliminates a chunk of data, there’s still a material amount of coordination overhead: query planning, block level access, slow remote reads, shuffle coordination, and so on. If you want to explore the inner workings of engines like Apache Spark or Trino, this blog breaks the design aspects down layer by layer.

Spark’s own documentation explicitly calls out that Spark applications can be used to “serve requests over the network,” and that multiple jobs may run concurrently when submitted from separate threads. The point isn’t that Spark can’t do it. The point is that Spark’s execution path was never optimized for a world where you need hundreds or thousands of concurrent low-latency requests with tight tail latencies. A good amount of these challenges are around networking (e.g high qps serving) and storage (e.g. indexing), which Spark does not address adequately since it is just a compute framework. Similarly, Trino inherits some of the same design limitations for these classes of queries. Trino exposes task-level concurrency settings and tuning concurrency is central to cluster stability.

These are not necessarily design flaws of Trino or Spark. They’re a reflection of design intent. They were never designed for these query shapes.

(b) Wide queries like analytics queries, adhoc exploration on operational databases built for OLTP

Now the agent pivots.

“Compare this user’s behavior to the last 6 months. Aggregate by cohort. Identify anomalies. Pull examples.”

If you point that at your operational database (or even a SaaS service’ REST API), you’ll get the worst of both worlds: critical queries powering your online apps & microservices are impacted by tail latency spikes. This is due to cache thrash and resource contention in the operational database, while the analytical workload is still slower than a system designed for scans (due to lack of columnar formats and other lake engine smarts). Anyone who has been on-call for a production database or a business-critical microservice knows whether this story has a happy ending or not.

(c) The new reality

So the architecture that made sense in 2020—lakehouse for analytics, operational DB for serving, warehouse for reporting—starts breaking down in 2025. AI agents cannot seamlessly use a single system and issues any kind of query shapes against it safely.

To be successful at scale, enterprises need something that is missing today: A serving system that can run low-latency database queries at scale directly on open lakehouse data, without causing outages on operational systems.

That system needs to be:

- fast for point lookups and selective filters to aid agent exploration or root-cause analysis

- safe for heavy scans without taking down production, to help agents crunch historical patterns

- elastic under unpredictable bursts, given the inherent non-deterministic behavior of AI agents.

- governed under the same policies as the lakehouse, to exert control over data privacy at a single central location.

That is the gap LakeBase fills.

3) What is LakeBase: a lakehouse serving layer, for both human-scale BI and machine-scale AI

From the outside, LakeBase looks boring in the best way. It exposes a Postgres-compatible endpoint, so your clients, BI tools, scripts, and agent runtimes can connect without bespoke connectors. Postgres wire protocol is a meaningful bar because the protocol isn’t trivial: it includes startup/auth negotiation, query/parse/bind/execute flows, and rich message semantics.

From the inside, LakeBase is intentionally not “an analytical engine that just opened a JDBC/ODBC port.”

The architecture is built around principles that database engineers learn early:

If you want low-latency and high concurrency, you don’t build around blocking threads and slow cloud storage access. You build around an event-driven server architecture that scales to high qps, degrades gracefully and handles backpressure with intelligent caching and indexing to speed up storage access.

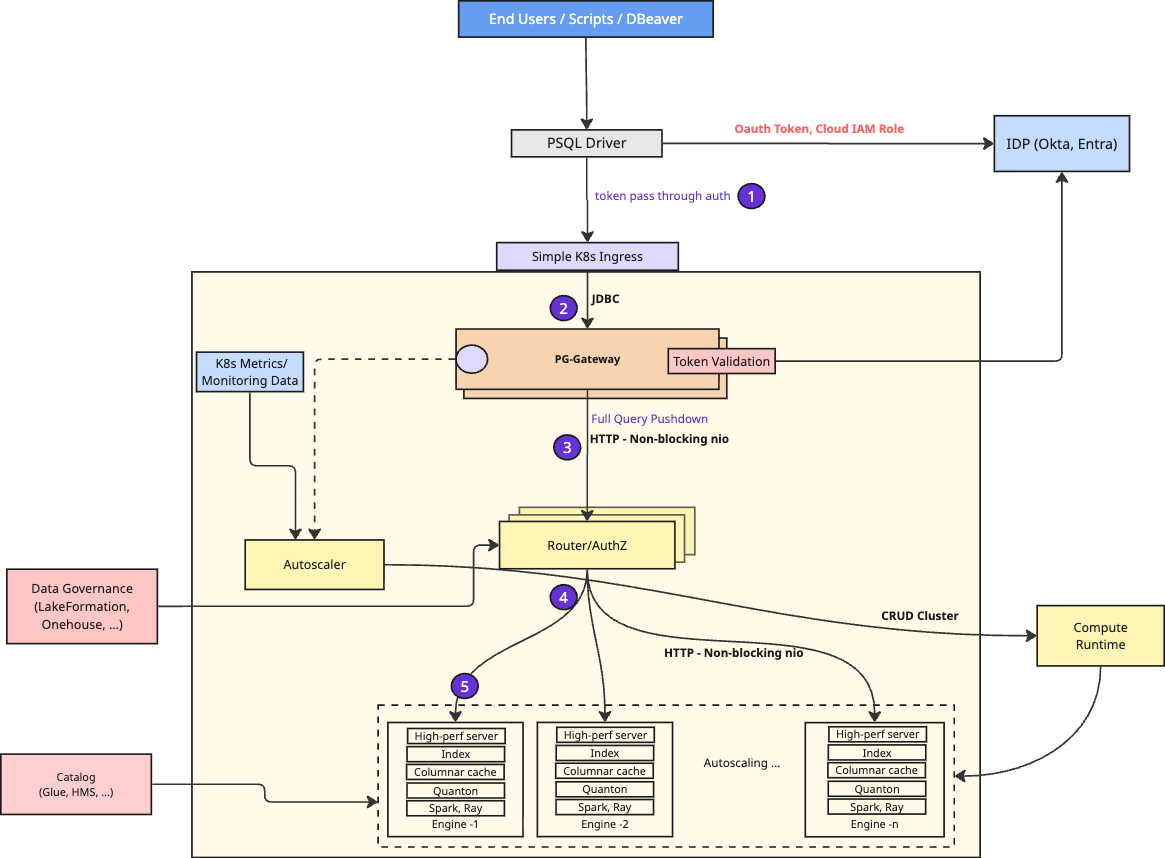

(a) A quick tour of the architecture

The diagram below is basically a picture of the set of things you must get right to serve low-latency queries at scale: authentication, authorization, routing, isolation, a high-performance network stack, elastic autoscaling, index management, consistent cache semantics and a really fast query engine.

At a high level:

- Clients connect using standard Postgres ODBC/JDBC tooling: The goal is “works with what you already have.” When you’re integrating agents, this matters: every framework already knows how to talk to Postgres; The PG-Gateway layer also handles authentication, integration with enterprise identity providers like Okta/Entra, before any request hits execution.

- Requests are then routed through a highly available routing service: The request then hits a stateless microservices layer that runs multiple instances of a gateway router service for load balancing and failure recovery. Meticulous engineering around connection management, request multiplexing, non-blocking I/O and high-performance event loops ensure this layer incurs close to zero queuing delays. The router also integrates with your existing lakehouse catalog like AWS LakeFormation, to perform authorization of requests before further execution.

- Queries are executed on a set of engines: Requests are ultimately routed to one of many engines with mechanisms to fail over requests when one engine is unavailable. Each engine consists of a distributed, columnar caching layer, distributed execution framework (Apache Spark/Ray), our high-performance query engine (Quanton) and most importantly, a high-performance http2/grpc server that can minimize request queuing and ensure low-latency execution. Engines can be vertically scaled using simple T-shirt sizes like S, M, L, XL – based on scale of the single largest query.

- High speed query execution within each engine: Each engine executes incoming queries as fast as possible using two key database techniques. Engine builds a distributed cache of frequently scanned, shuffled and final query results, with high-bandwidth inter-node access mechanisms. Furthermore, Hudi and Iceberg tables are indexed to speed up access and dramatically reduce the amount of data to scan. Even our in-memory cache representations build similar indexes & statistics, to keep each query scan task reading the fewest bits as possible, even if it’s from the distributed cache.

- Horizontal Autoscaling based on cluster utilization: In addition to vertical scaling engine sizes, the autoscaler component monitors query execution across the engines and gets feedback loops from the PG-Gateway layer about query latency. It then uses these signals to invoke Onehouse Compute Runtime APIs to spin up new engines to balance load or shut down unnecessary engines to improve efficiency.

If you’ve built a low-latency serving system or a sharded microservice before, the above should feel familiar. That’s not a coincidence. The “lakehouse” world has spent a decade refining analytical query execution, but has not yet absorbed solutions to problems from the “serving” world around concurrency, tail latency, admission control, backpressure, etc. LakeBase is an attempt to bring those learnings and disciplines to the lakehouse.

(b) Why we talk about HTTP/2 and networking in a database announcement

Because when QPS goes up, the network stack becomes one of the most critical components of your database engine. HTTP/1.1 has well-understood head-of-line blocking characteristics that become painful when you try to multiplex many request/response streams. HTTP/2’s multiplexing directly addresses request-level HOL blocking at the protocol level (transport-level HOL over TCP is a separate issue). We’ve written about some of these issues extensively here, in the context of cloud storage access.

We’ve lived through this lesson in other domains. If you’ve ever debugged “why does my analytics engine collapse at 2k concurrent connections,” the answer is often not “optimize SQL,” it’s something like “stop blocking the server on I/O waits.” LakeBase treats that as table stakes.

(4) LakeBase’s core technical bet: database building blocks on open table formats

Now that we have spent time on the overall architecture, let’s dig a little deeper into the fundamental technical limitations LakeBase is addressing and why those problems matter.

(a) Is this just the lakehouse ‘hammer’ looking for a ‘nail’?

We’ve already covered why letting AI agents query production databases directly is risky. The obvious alternative is separate Postgres/MySQL instances or specialized systems, but those break down at scale. The case for serving agents from the lakehouse is straightforward:

- Scan performance matters for enterprise AI. RDBMS top out quickly, and distributed systems like Elastic/OpenSearch struggle with large, scan-heavy workloads. That’s why every Fortune 500 relies on a data warehouse or lakehouse for analytics and data science.

- Cloud storage is operationally simpler. Engines like ClickHouse and StarRocks deliver fast scans, but they favor stateful, local storage they fully control. That makes them harder to operate and scale. Most teams adopt them only when the lakehouse can’t meet performance needs, accepting higher operational burden as a tradeoff.

- The data is already in the lake. Most companies have invested heavily in building, governing, and securing a data lakehouse to democratize access to data. That same foundation is critical for the AI agent lifecycle—exploration, iteration, and figuring out what a useful agent should even do.

- Lakehouse unit economics are unmatched. Cloud storage offers the lowest-cost, most scalable storage, paired with highly efficient compute (headless execution, vectorization). Much of the ingestion and transformation for AI agents already happens on the lakehouse. Given how read-heavy agent “tool” queries are, the lakehouse can also serve as a low-latency access layer.

The conclusion is simple: the lakehouse should remain the source of truth, with a stateless, high-performance serving layer on top. That lets teams focus on building BI and AI value instead of running yet another specialized database.

(b) Adaptive columnar caching that avoids unnecessary compute overhead

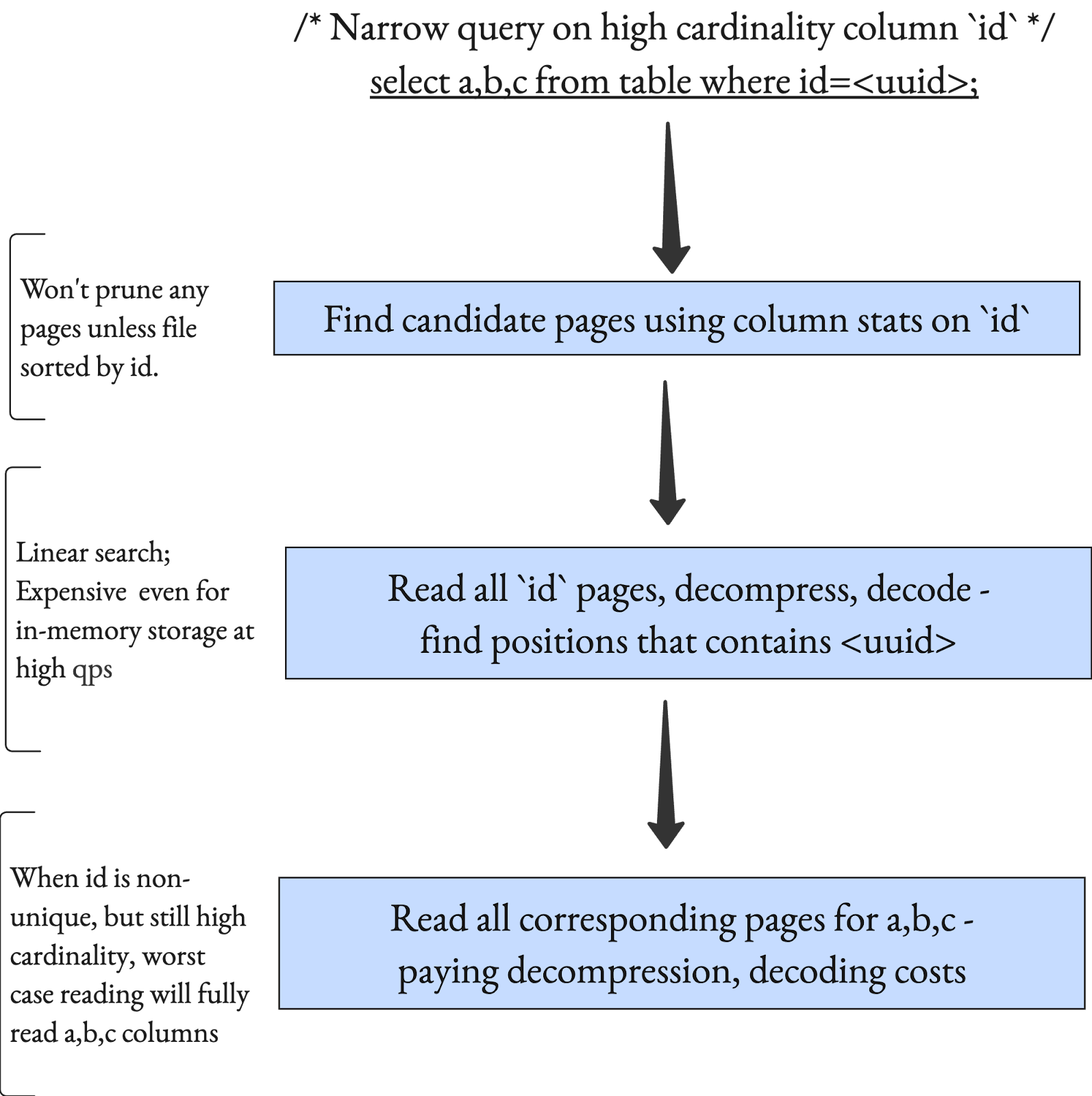

Many lakehouse engines cache data at the file-system level to reduce network I/O. This helps, but it targets the wrong bottleneck. With modern columnar formats like Apache Parquet and today’s cloud networks, performance is no longer network-bound—it’s CPU-bound. Even when Parquet files are cached in memory or fast SSDs, every query still pays the CPU cost to repeatedly decompress and decode pages, doing work proportional to O(number of records per page). The figure below pares down the cpu costs involved for narrow queries, even when the file is fully cached in-memory. The same access pattern is also executed on cloud storage and incurs ~10+ storage API calls each costing 10s of ms potentially. While data structures like bloom filters help narrow down the first block, it does not fundamentally alter the cpu costs/overheads when low latency is the desired goal.

LakeBase avoids this by using different representations for storage and cache: open formats like Parquet on storage, and optimized in-memory/on-disk representations (e.g., Apache Arrow based layouts, with stats and smarts) in the cache. This lets LakeBase exploit modern local hardware such as NVMe SSDs, dynamically materializing data in columnar or row-oriented layouts, with or without compression & encoding, based on access patterns. Unlike traditional file-level caches, LakeBase adapts I/O to the medium itself, reading columns in parallel and leveraging SSD-friendly random access to achieve microsecond-level latencies. Existing lakehouse engines, by contrast, perform essentially the same I/O whether data lives in memory, SSD, or cloud storage.

(c) Transactional caching consistent with table commits

This is subtle, and it’s where most naive “cache the lakehouse” projects die. If you cache results or data pages without an explicit relationship to the table’s commit timeline/snapshot, you either:

- serve stale data without knowing it, or

- rebuild caches too aggressively and lose the benefit.

Open table formats give you a hook here: commits advance snapshots (Iceberg) or timelines (Hudi). LakeBase ties cache correctness to those transactional boundaries, so the cached state remains consistent with commits. This is very similar to how a buffer pool is transactionally consistent in a database.

(d) Distributed caching for hot data and repeated query patterns

When working with large data volumes on expensive media like memory and SSDs, cache efficiency is critical. A purely node-local cache causes the same files or records to be cached redundantly across nodes, wasting capacity and sharply limiting the effective working set. In practice, agents, humans, and dashboards repeatedly issue the same queries, making shared caching of repeated executions essential.

LakeBase implements a distributed cache across engine nodes, so any given set of records is cached only 2–3× across the cluster for redundancy and failure handling. If data is not present locally, records are fetched from remote nodes with query predicates pushed down to minimize data movement. By contrast, Spark’s cache must read the entire remote block to satisfy a remote cache hit. LakeBase also includes a query result cache that uses table-format metadata to determine result validity, ensuring cached results remain correct and consistent.

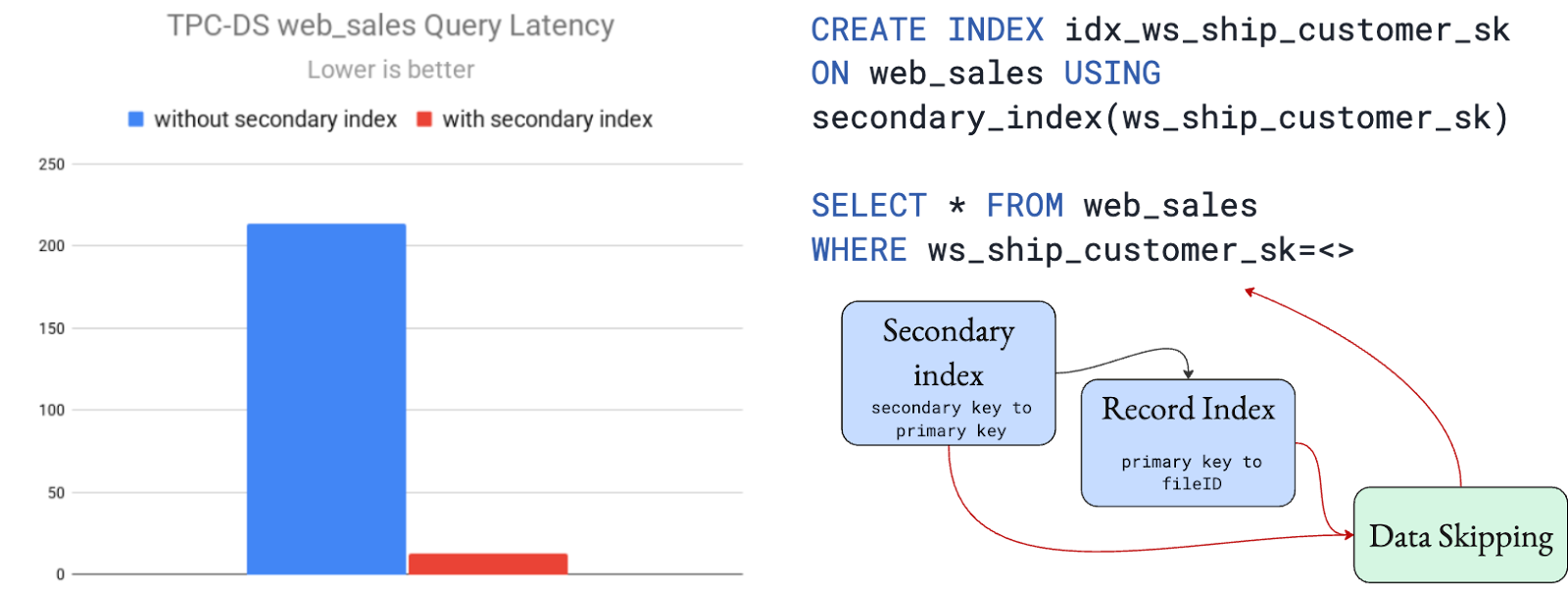

(e) The only lakehouse serving layer with indexes

Lakehouse systems have historically been optimized for scans. Even a simple point lookup often degenerates into a linear search across files or partitions. This gap has persisted for years, despite a clear need for more selective access to the same data—for example, debugging by humans, root-cause analysis by AI agents, or drilling from a broad analytical slice down to a handful of specific records. A market analyst might scan an industry’s performance and then immediately need to fetch records for a few ticker symbols to validate a hypothesis. On a traditional lakehouse, that second step is disproportionately expensive.

LakeBase employs global record-level and secondary indexing techniques across your tables, proven and powering production already at trillion-record scale. Coupled with intelligent caching of the index data on the distributed cache, this can shave off 95% of latency incurred when performing point-lookups on a lakehouse. These gains can be realized even at modest table sizes like 1TB, and only increases as your table data scale grows.

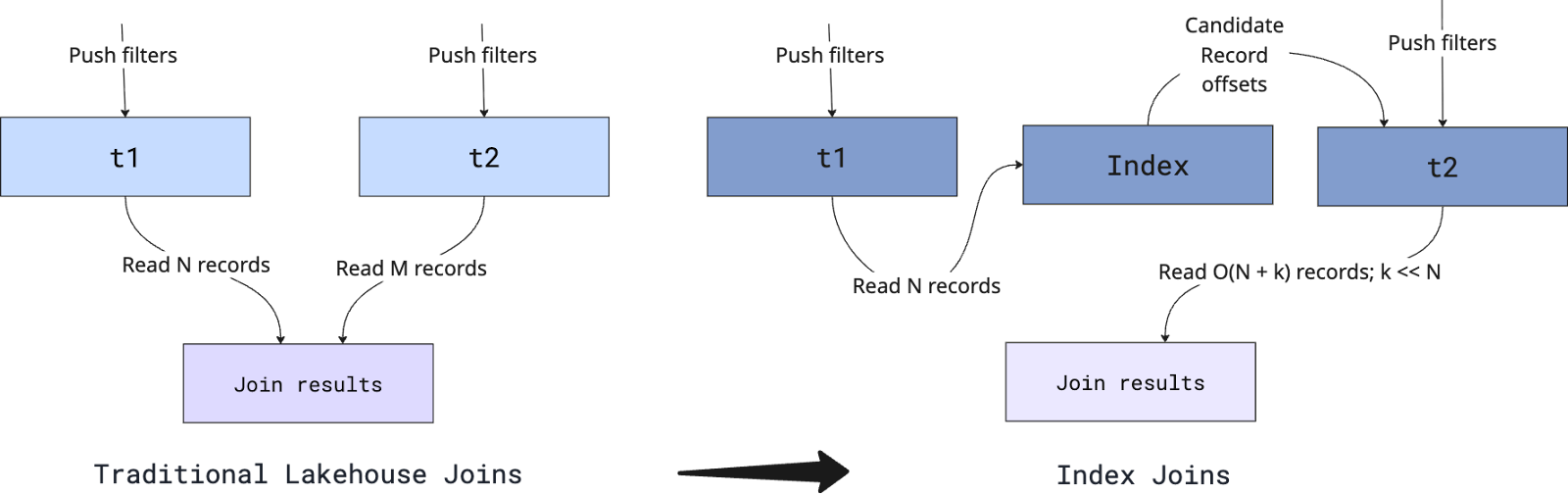

(f) O(N) Index Joins fundamentally change cost structure for Agent data exploration

Indexes don’t stop at accelerating point lookups. They also fundamentally change how joins execute in LakeBase. We keep saying we want AI agents to explore data quickly. But real exploration almost always involves joins. An agent filters a dimension table on some high-cardinality predicate, identifies a small candidate set, and then needs to fetch matching records from one or more large fact tables. Sometimes it’s DIM → FACT. Sometimes it’s FACT → FACT. Either way, joins are not optional, they are central to agent reasoning.

On a traditional lakehouse engine like Spark and Trino, these joins are executed using broadcast, shuffle hash, or sort-merge strategies. Let’s define some terms clearly:

- N = number of rows in table

t1 - M = number of rows in table

t2

In most distributed lake engines, even with filtering, the execution path requires scanning and repartitioning large portions of both tables before producing the final result. The cost is typically on the order of O(N + M) in terms of data scanned and shuffled, and under skew or spill conditions can degrade close to even O(N x M) further in practice. The key point: the work scales with the size of both input tables. LakeBase introduces a different physical execution model: index joins built on table-global record-level indexes (RLI) and secondary indexes (SI), that are proven up to petabyte scale tables.

Instead of scanning two large tables t1 (size N) and t2 (size M), we:

- Apply selective filters on

t1(for example, a filtered dimension table). - Let K = number of qualifying rows after filtering t1, where typically K ≪ N.

- For each of those K keys, use a global index to directly locate matching records in

t2. - Fetch only the necessary rows from

t2, avoiding full-table scans and large shuffles.

Now the join cost scales roughly with O(K) (plus indexed lookups), not O(N + M). In other words, performance is proportional to the size of the filtered working set, not the raw table sizes.

This isn’t just a new join algorithm, it changes the cost model. Databases have long supported index joins, but they were built for local storage models. Cloud object storage has different constraints and new join strategies only work if indexing, caching, and networking are designed for that reality. LakeBase makes global indexing a first-class primitive on open lakehouse tables and combines it with distributed caching. This builds on the secondary indexing innovations introduced in Hudi 1.0 and extends them to formats like Iceberg, turning the lakehouse into an interactive database for agent workloads.

(g) Where Quanton and Apache Spark fit: Spark is the cluster manager, Quanton is still the engine

There’s a reason I’m being unusually explicit here: LakeBase is not “Spark serving.” Spark appears in the architecture as a cluster orchestrator because it’s a familiar operational substrate. A framework like Ray could get the job done as well. But the core of what makes LakeBase work—planner, optimizer, execution, caching, and storage semantics—has been fundamentally reworked by other OSS, homegrown components.

LakeBase query execution is powered by Quanton, the same set of innovations we’ve been building for next-generation lakehouse compute. LakeBase queries benefit from the same incredible compute efficiency Quanton brings to SQL ETLs, while other components realize the dream of low-latency serving from the lakehouse.

(5) Show me some real numbers

While many benefits of the lakehouse architecture such as storage/compute efficiency and Quanton’s performance are already well covered by existing benchmarks, one critical dimension still needs to be proven: serving performance. Throughout this post, we’ve emphasized the gap around low-latency access as the missing piece for lakehouse-based serving. This section is where we put that claim to the test.

We focus on three questions:

- How does LakeBase perform on real production workloads, not synthetic microbenchmarks?

- How does it behave across narrow (highly selective) and wide (analytical) query shapes?

- How does it compare directly to incumbent managed lakehouse services like AWS Athena and Databricks?

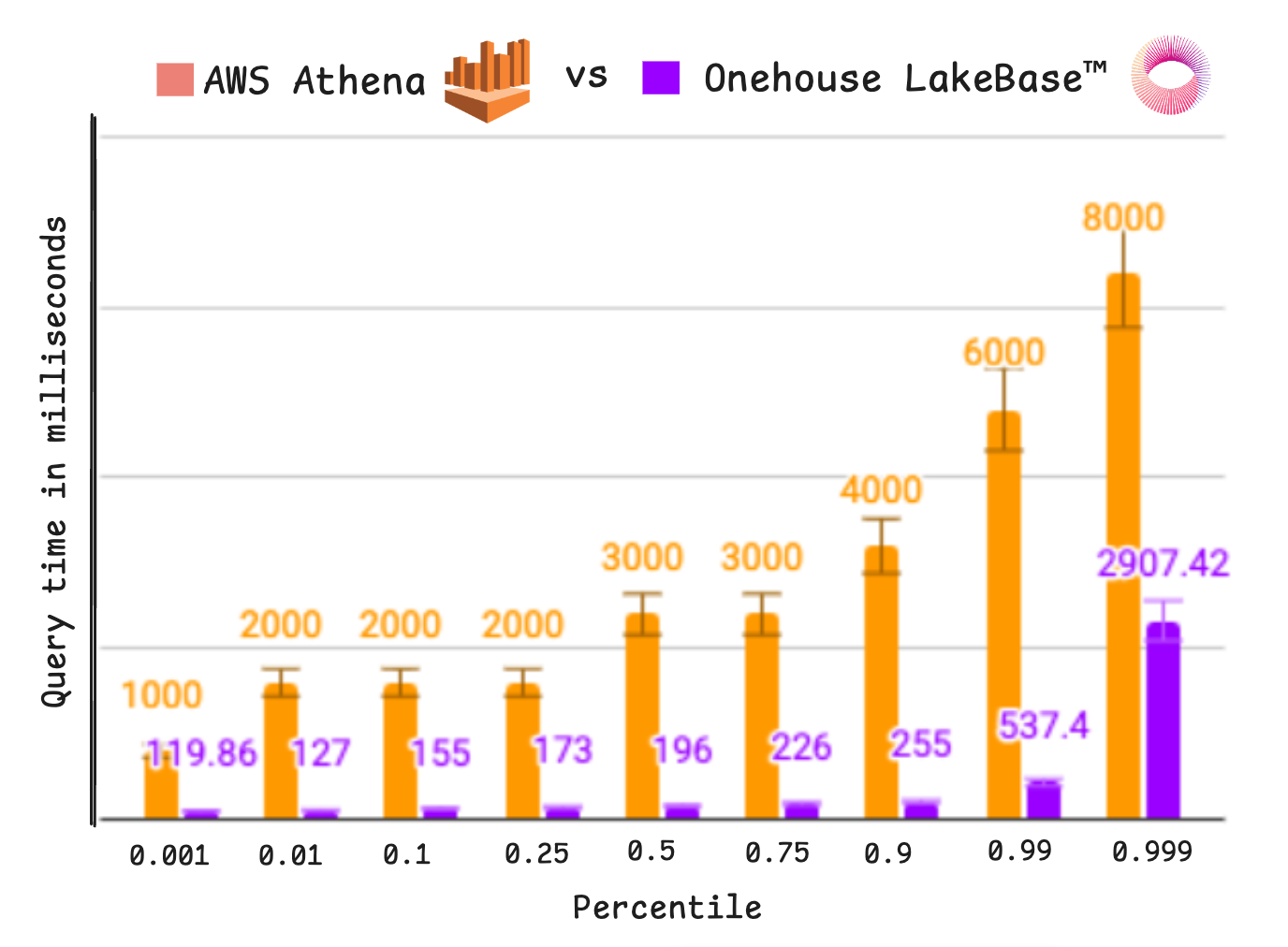

(a) Customer benchmark: replacing Athena in production

We are actively working with a large enterprise customer to deploy LakeBase in production, specifically to reduce the latency of their Athena workloads. The results below combine representative queries from a real, petabyte-scale production lakehouse with trace-driven replay of Athena query logs to simulate realistic multi-user concurrency. Under identical workloads, LakeBase consistently delivers materially lower tail latencies, including beyond P90, while providing very consistent low-latency performance up to the p90.

Figure: Customer AWS Athena 12 hour query trace replay — latency histogram (P50 / P90 / P99) - across 570 production tables

(b) Narrow vs. Wide: breaking down query shapes

The figure below breaks down representative customer queries based on whether queries are narrow (1, 2, 4, 11) or wide shaped (3, 5-10). Narrow queries are accelerated using indexes and caching. Wide queries that scan more data or do not possess selective filtered are accelerated by the Quanton compute engine and caching. The key takeaway is that a single system can support both query types and accelerate each with the different database techniques.

Figure: Latency comparison with Athena, using representative queries spanning ~1PB of data

(c) Against Leading Lakehouse Services

We also evaluated LakeBase directly against Databricks SQL to see how it fared on these narrow queries that the emerging AI systems may throw at the lakehouse. To measure this, we created dimension and fact tables using the LakeLoader tool and tested low-latency narrow query access patterns on them. Specifically, the fact table had around ~1TB of parquet data on copy-on-write tables with 100 partitions. There are two dimension tables - a very small table with just 462 entries and a larger DIM table close to ~100GB. The test demonstrates consistent 6x performance gains against Databricks SQL Serverless lakehouse for these narrow queries that are so crucial for frictionless AI agent loops.

Many lakehouse vendors including Databricks implicitly acknowledge the serving gap and recommend hybrid patterns:

- Keep analytics on the lakehouse

- Push subsets of data back into operational databases

- Serve low-latency queries from there

This “reverse ETL” model works, but at the cost of additional complexity, failure domains. It is, effectively, a duct-taped architecture: analytical system over here, serving database over there, with data constantly shuttled between them.

We take a different view: If the lakehouse is the source of truth, then database primitives like indexes, low-latency access paths, and transactional caching should exist natively on top of it, not bolted on via data movement. Serving from the lakehouse directly eliminates the architectural split-brain. Given AI agent context data is very read heavy, we think this approach can reduce complexity over other approaches.

7) What’s coming

Two things can be true at once:

- We are excited about what LakeBase does today.

- The most interesting work is what LakeBase enables next.

Here’s the direction.

(a) Open-sourcing parts of LakeBase

We intend to open-source meaningful pieces over time. We hope our track record and commitment to openness speaks for itself. If you’re a serious organization that wants to collaborate, reach out. The fastest way to build something durable is to pool engineering resources with teams that have real workloads and sharp opinions.

(b) Toward HTAP: columnar today, row-oriented when it matters

Most lakehouse data is columnar—for good reason. Columnar layouts are ideal for large scans and analytics. But serving workloads, especially the “needle-in-a-haystack” queries common in agent exploration, need fast, selective access paths that are fundamentally row-oriented.

Long term, our goal is to put a HTAP spin on the lakehouse: columnar for scans, row-oriented for point lookups. The lakehouse architecture makes it plausible to materialize both representations at scale and dynamically choose the right one at runtime based on the query plan.

(c) Scaling into “millions of QPS” territory

I’m going to say this carefully, since “millions of QPS” is a phrase that gets thrown around casually. It’s also a phrase that, in real systems, forces you to confront the hard parts: tail latency, cache invalidation, backpressure, multi-tenancy isolation, and failure modes. While LakeBase today can achieve generally higher qps than lakehouse engines, and reach 1000s of qps with 2-3 engines horizontally scaling out. But, this is not enough and we are at-least 100x behind the desired scale/cost curves we’d like to operate at.

Thankfully, this is not our first time building serving systems that must meet large scale. Armed with hard earned lessons from scaling operational databases for hundreds of millions of users at Internet companies like Linkedin or Uber, we are excited to keep pushing the throughput ceilings for LakeBase into these planet-scale ranges.

8) Call to action

If you’ve been building agent-facing data systems or operating specialized systems for just low-latency queries, you already know that it doesn't scale cleanly. You can keep moving data into specialized systems and maintain an ever-growing tangle of pipelines, governance workarounds, and operational burden. Or you can serve from where the data already lives, in the lakehouse, with a layer designed for the realities of the AI era.

LakeBase is that layer.

Next steps:

- Sign up for the LakeBase webinar

- Contact us for a free trial

If you’re the senior engineer who owns the consequences of your company’s data stack, this is a good moment to re-think “serving” as a first-class primitive of the lakehouse, not a workaround reverse-ETL-ed after the fact.

— Vinoth

Read More:

Announcing Apache Spark™ and SQL on the Onehouse Compute Runtime with Quanton

Subscribe to the Blog

Be the first to read new posts