Inflated data lakehouse costs and latencies? - Blame S3’s choice of HTTP/1.1

TL;DR

Introduction

Over the past few years, data lakes have undergone a fundamental shift in how they are built and operated. Increasingly, organizations are moving away from traditional distributed file systems and embracing object storage platforms such as Amazon S3, Google Cloud Storage (GCS) and Azure Data Lake Storage as the backbone of their data lake architectures. This transition is driven by the scalability, durability, and cost-efficiency that these storage systems offer—making them the natural choice for modern analytical workloads.

Unlike distributed file systems with tightly coupled binary protocols, cloud object storage systems rely on RPCs (Remote Procedure Calls) over HTTP/TCP—a difference that has real performance and cost implications. In this blog, we bring out the real world performance implications of S3 using HTTP/1.1 while GCS fully adopting HTTP/2 for direct object transfers.

We take a closer look at the evolution of the HTTP specification, with a particular focus on how HTTP/2 improves connection management and multiplexing, reducing both latency and the overhead of maintaining multiple TCP connections. Our analysis also highlights gaps in widely used HTTP client implementations—most notably in the AWS SDK’s handling of HTTP/1.1. Backed by production data, we observed up to 15× higher latencies when accessing S3 compared to running an equivalent workload on GCS, revealing the real-world impact of these implementation details.

Finally, we’ll share how these insights shaped our approach —and challenges—in building the Onehouse lakehouse platform. We also discuss a few optimizations that we built for S3 access to negate some of the inefficiencies with HTTP/1.1 implementations.

HTTP Protocol Stack

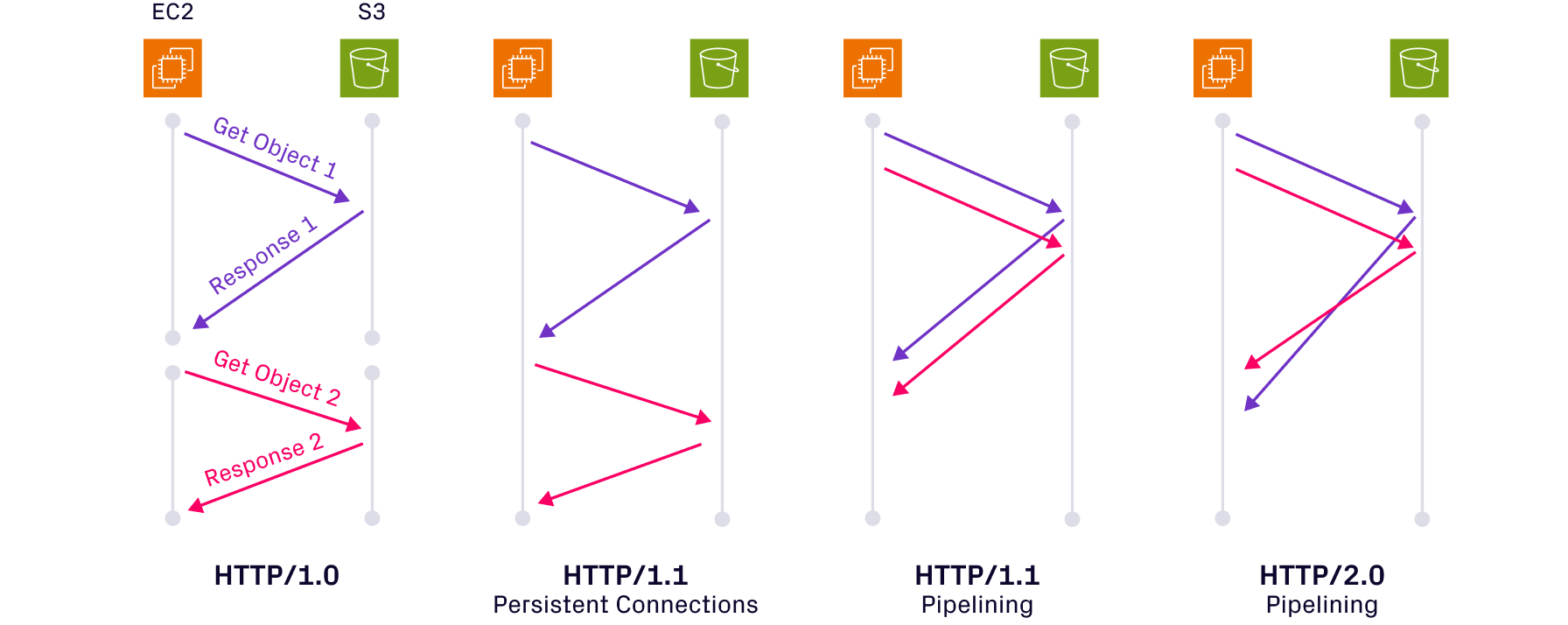

There are several layers of protocols to control how S3 or GCS objects can be downloaded or uploaded. This layered design allows developers to issue Remote Procedure Calls (RPCs) that feel simple—such as a GET request to download an object or a POST request to upload one—while the underlying complexity of connection management and data transmission is handled by the networking stack.

The application layer interacts with the HTTP semantic layer via GET,POST,PUT or DELETE requests. HTTP defines a structured and standardized way for clients to request and transfer data. The client’s HTTP layer establishes a session with a peer, typically the frontend of the cloud storage system. Even in a private network completely managed by a cloud provider, there are multiple network hops between the compute platform (e.g., EC2 node) and the storage system (S3). The figure below illustrates a possible deployment for an application running on an EC2 node interacting with AWS S3. Transport protocols, such as TCP/ QUIC ensure that the end to end connectivity can be established and maintained to reliably transfer data across the endpoints using congestion control and packet retransmission. The lowest layers, network (IP) and the link layers ensure that the data packets can be routed across the heterogeneous physical network in a best effort manner.

How lakehouse operations are affected by HTTP calls

In object storage systems, every object read or write is essentially an HTTP transaction. This means the performance characteristics, latency, and throughput of these systems are deeply influenced by HTTP’s behavior—and by its evolution over time. Modern data lakes built over these cloud storage systems have also evolved significantly over recent years. To understand quantitative impact on the scale of RPC calls to object storage, we obtained stats from ~2000 pipelines ingested and managed by Onehouse totaling a few PBs of Apache Hudi tables.

With the increase in transactional workloads, a significant portion of pipelines are mutable, i.e., the records ingested may contain updates or deletions for existing records and often constitutes up to 70% of total compute spend on ELT/ETL pipelines. Mutable pipelines could have high write amplification, as the update and delete records might be spread across multiple files and partitions of the table. When an update or delete is applied to a file, either inline during ingestion or async during compaction, the operation requires full read (GET) followed by a write operation (POST) against cloud storage to produce new file versions.

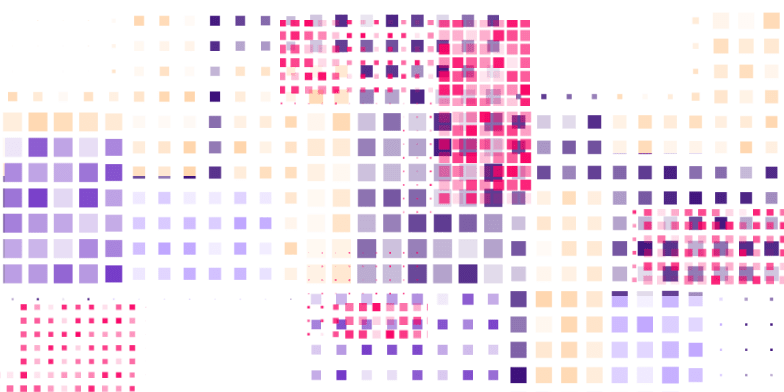

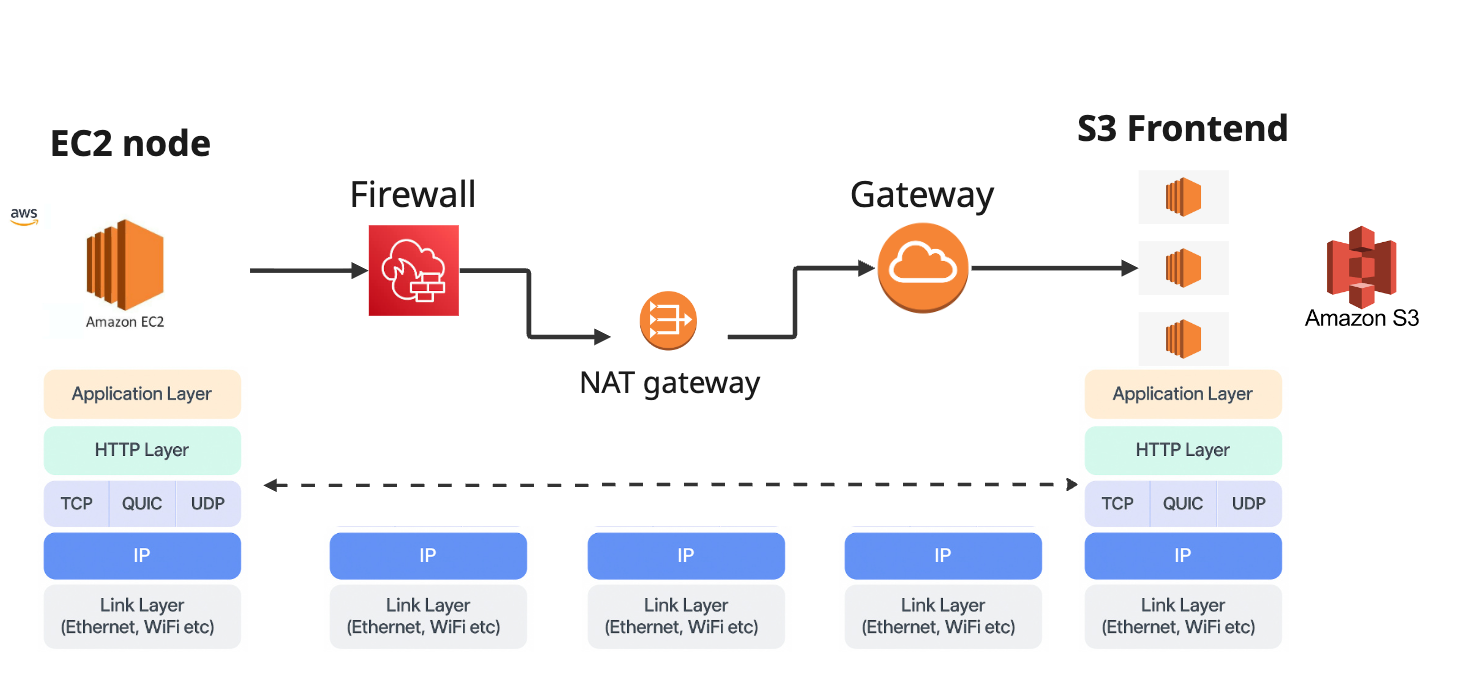

The figure on the left below shows the complementary CDF of the number of files modified across 1000s of pipelines for 1 week of runs. In about 50% of the pipeline runs, almost 500 files are modified in a single commit. This translates to 500 GET and POST calls in order to read the existing file, modify/merge the appropriate records and write the new file version back to storage for a single pipeline run. The right figure shows a similar distribution of the number of files cleaned (deleted) where we see >10% of the pipeline runs remove about 5000 files. While the cleaner service for Hudi runs less frequently than ingestion, it is primarily triggering the HTTP DELETE call for 100s to 1000s of objects (files) depending on the scale of the pipeline. More than 75% of these pipelines sync data at a frequency of 30mins or less. The scale of RPC calls to object storage will only increase as pipelines move away from batch to streaming, where syncing happens incrementally but more frequently.

As more and more warehouse workloads move to data lakehouses, users' expectations for query performance on lakehouse tables is also higher. The use of table management services such as compaction and clustering is very common in order to maintain well-sized files and sorted data layouts. Within Onehouse, we provide incremental clustering that intelligently only rewrites files that were modified since the last clustering run. We still see ~20% of the pipeline runs read, sort and write more than 250 files in a single clustering run.

Another important trend is that data lake formats have started using extensive metadata for active files, column stats and indexes to improve performance. Such metadata is typically stored as objects (files) within object storage itself. The access pattern for metadata is a lot different than the access pattern for the data objects. For instance, in the figure above (right) we compare the amount of bytes downloaded (in GB) and the number of GET calls from the files for a single compaction operation on the data table vs a single indexing operation – looking up files using record level indexes within the metadata table for a pipeline writing to a Hudi table. The data was obtained for a pipeline ingesting to a 1PB table from a large-scale enterprise customer. The amount of bytes downloaded from the metadata table is a lot lower than the bytes downloaded from the data table. However, the number of GET calls are comparable since metadata access involves several GET calls over different byte-ranges. In the case of Hudi, metadata is stored in HFile format, and only appropriate blocks within a HFile are read that contain the required metadata.

Most of the data lake write and read operations rely heavily on the performance of the object storage, and the performance of the underlying HTTP requests are a key part of that. Slow or unreliable HTTP performance can heavily impact the compute costs as compute cycles are idle while objects are listed, fetched or uploaded.

Evolution of HTTP

While the HTTP semantics have largely remained consistent, the protocol itself has evolved significantly over the years. Today, more than 90% of all internet traffic flows over HTTP—even though it was originally designed for transferring files.

Modern applications that are highly sensitive to latency and throughput, such as messaging platforms, video streaming, and video conferencing use HTTP as well. The ubiquity is reinforced by the vast infrastructure built around it: CDNs, frontends, proxies support HTTP. This deep integration makes it nearly impossible to replace, even for specialized use cases. Although designed for video streaming/ conferencing, protocols like RTP saw limited adoption and never displaced HTTP.

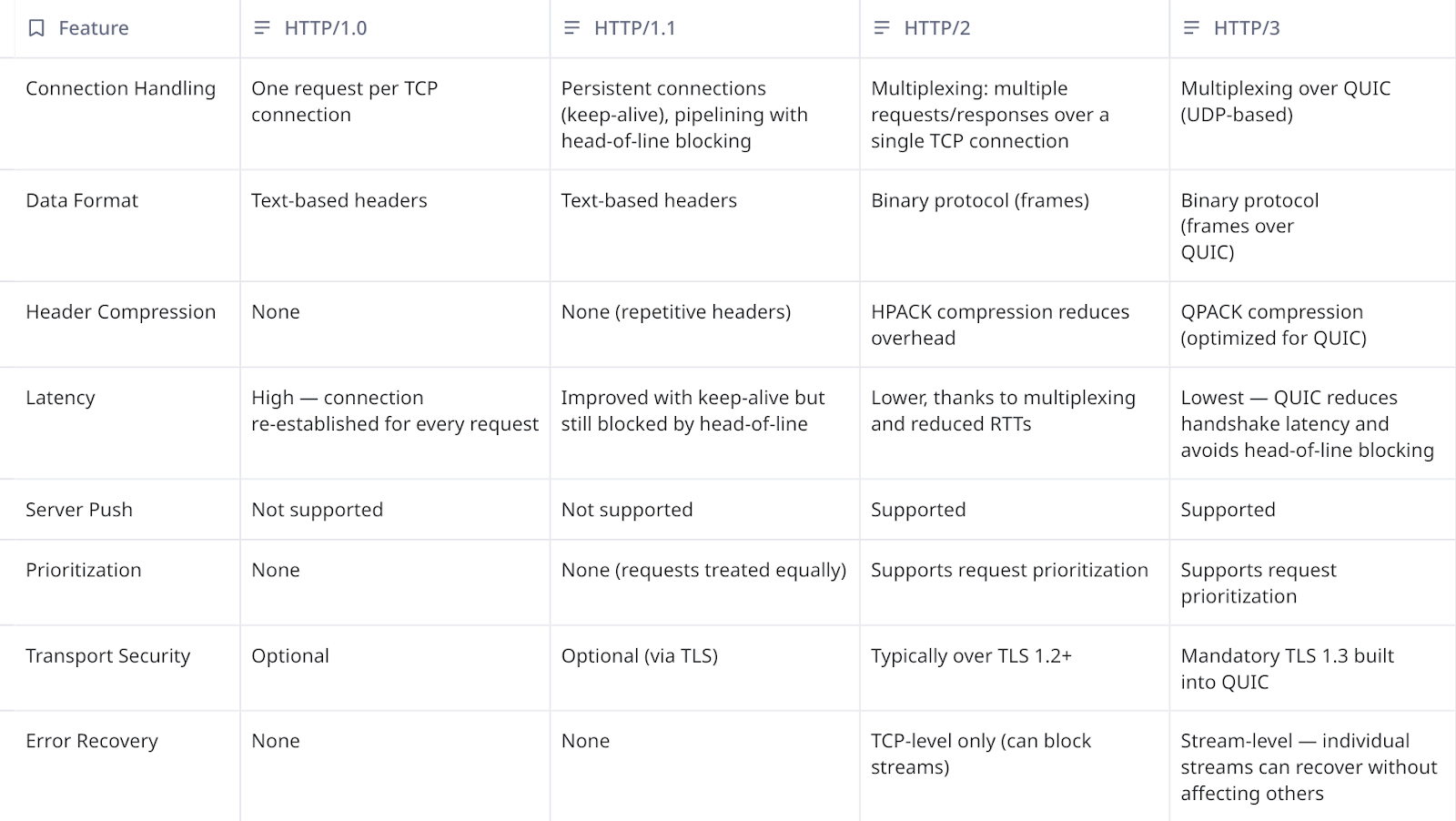

The table below highlights key improvements introduced as HTTP evolved from version HTTP/1.0 to HTTP/3. The main takeaway from the table is that HTTP/2 marked a step-change in the protocol, delivering significant performance improvements over earlier versions of HTTP. HTTP/2 improved connection management by multiplexing requests and responses across each TCP connection. Besides that, HTTP2 was the first version moving away from text-based protocol to an efficient binary encoding for data and improved compression for headers. It was also the first version to support prioritization across requests and add the ability to push resources from server to client proactively.

HTTP/2 was standardized largely based on Google’s SPDY protocol, refined through real-world deployment on Google’s large-scale infrastructure and the Chrome browser. By leveraging request multiplexing, HTTP/2 significantly reduced latency and improved throughput—handling far more requests per second than its predecessors. It also optimized resource usage with binary framing and advanced compression, making it more efficient in both memory and CPU utilization. Specifically, Google reported about 27-60% reduction in latencies for the Top 25 website with SPDY compared to HTTP/1.1.

Improvements in connection handling

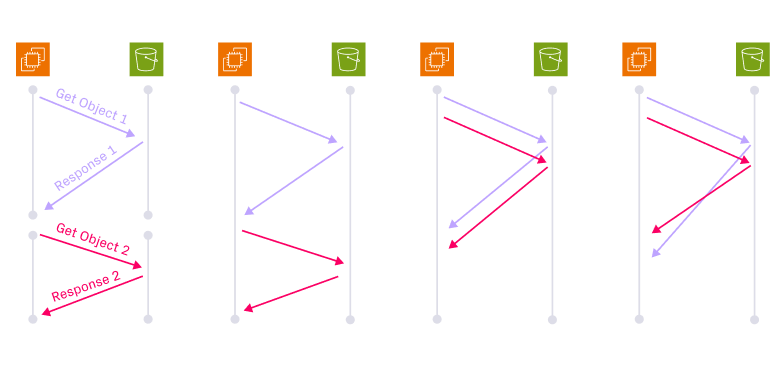

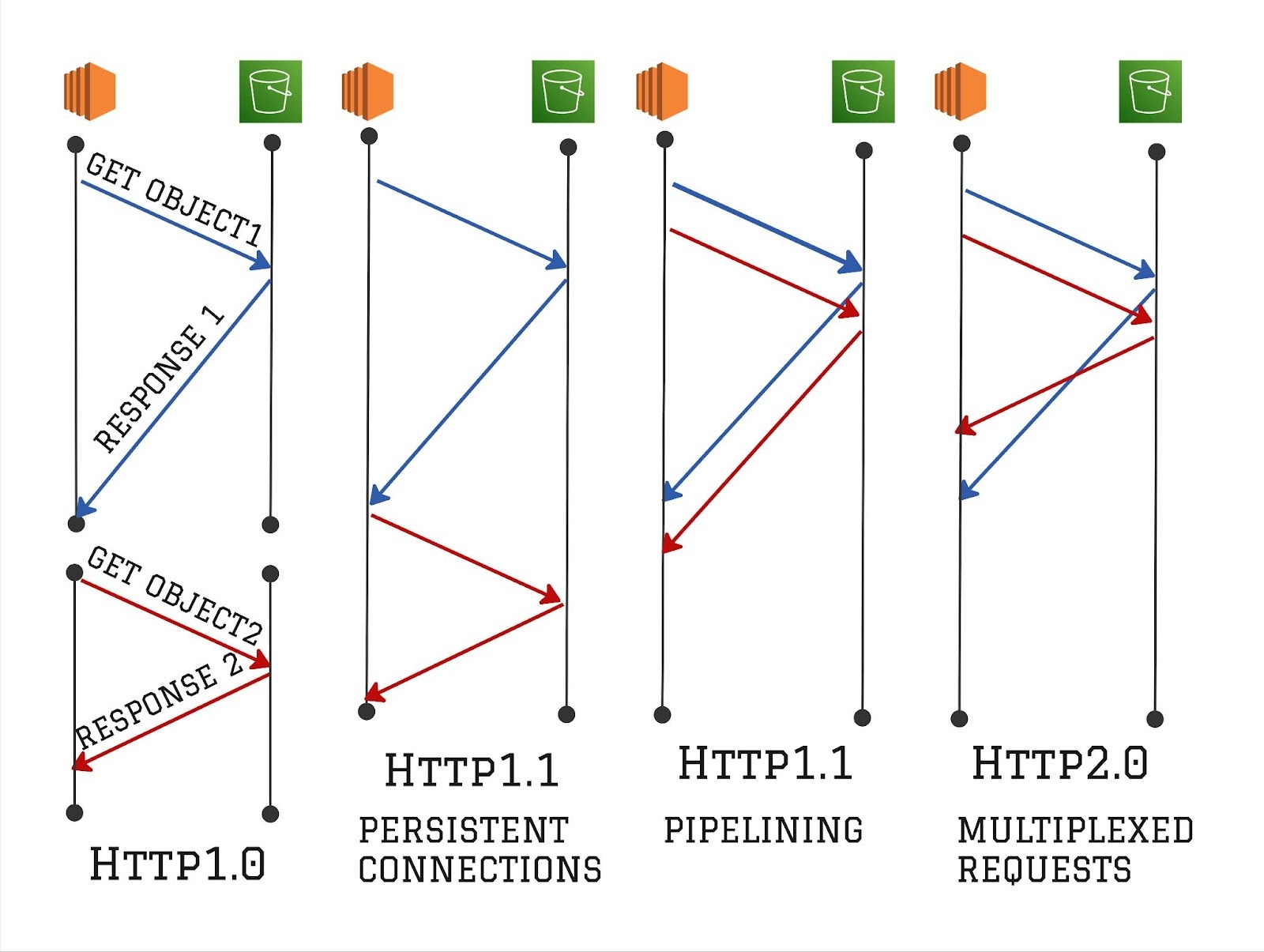

Among all the improvements, connection management is the most critical in terms of impact on performance. The figure below depicts how different HTTP versions handle multiple requests and responses over TCP connections. HTTP/1.0 had a naive connection management, where each request creates a separate TCP connection. It was possible to use persistent connections using HTTP Keep-Alive headers to allow the reuse of TCP connections across HTTP requests. However, persistent connections became default and widely adopted with HTTP/1.1. This allowed subsequent requests to reuse an existing TCP connection, avoiding the need to recreate TCP connections.

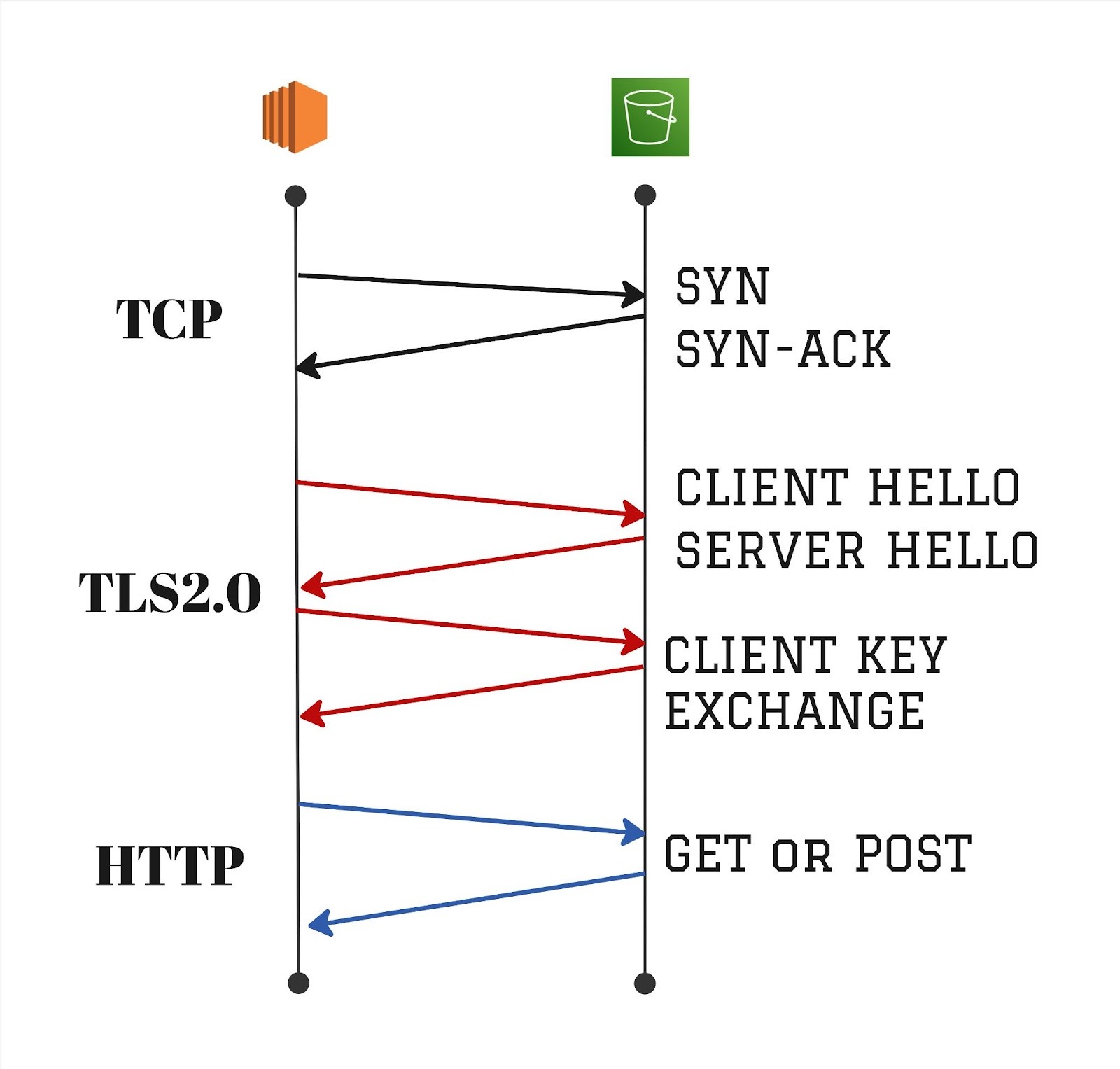

As shown in the figure below, there could be 3-4 round trips for a typical TCP connection establishment before the HTTP request can even be sent, so the cost of having to use a new TCP connection for a HTTP request can increase latencies.

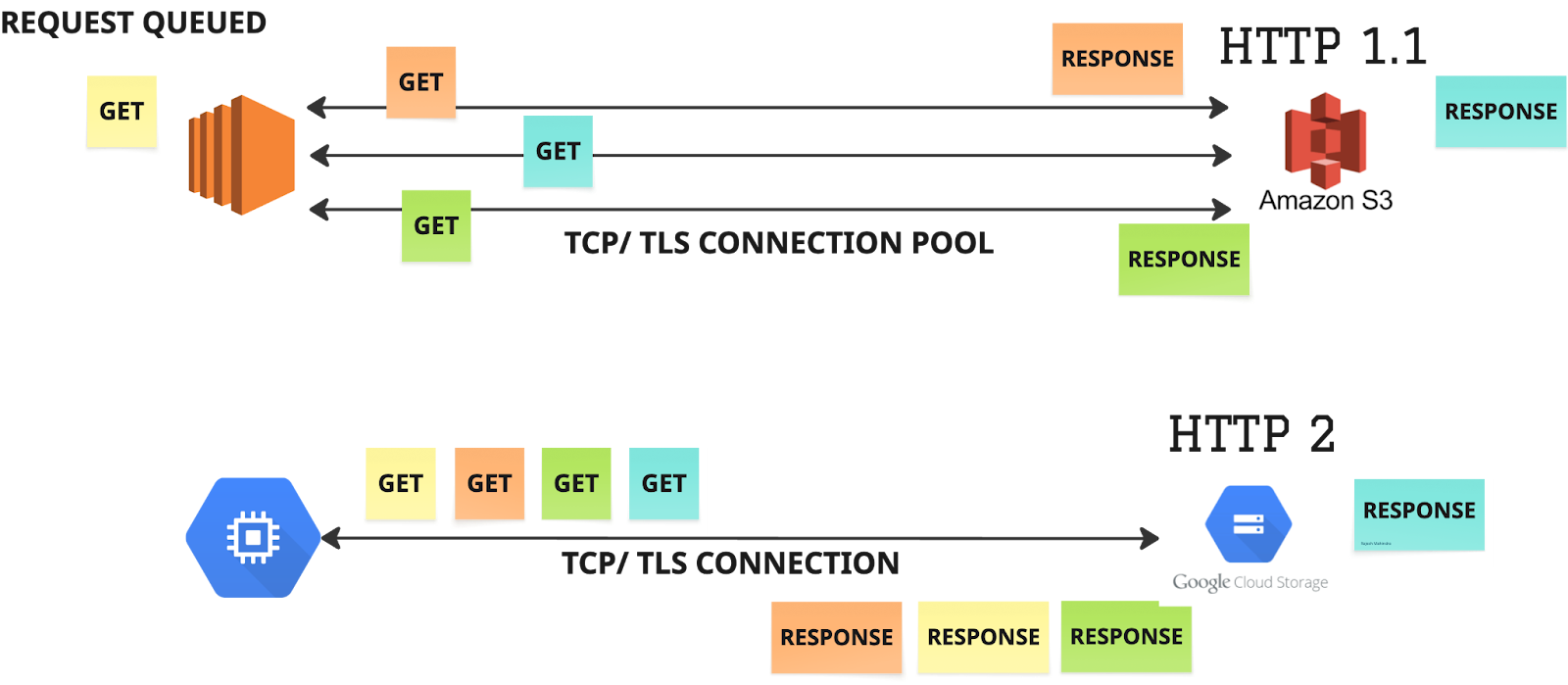

When multiple HTTP requests are made concurrently, HTTP/1.1 implementations had to rely on a TCP connection pool to be able to send those requests at the same time. To solve the problem of having to create a new TCP connection if the existing one is being used for a HTTP request, HTTP/1.1 spec later introduced pipelining. Multiple concurrent HTTP requests can be made on the same TCP connection, instead of requiring a separate TCP connection for individual requests. However, an important drawback is that the responses are delivered in the same order as requests. This can cause head-of-line blocking where larger responses could block smaller responses. For instance, if there are back-to-back HTTP GET requests for two objects that are 1GB and 1MB respectively, the response for the smaller object will be blocked until the larger object is completed.

HTTP/2 natively supports multiplexing concurrent requests over the same connection, such that the responses can be received out-of-order. It still suffers from head-of-line blocking at the TCP layer. If a TCP packet is lost, all the active HTTP requests get blocked until that packet is retried and successfully received by the other endpoint. HTTP/3 solves the head-of-line blocking at the transport layer by using QUIC instead of TCP, which is able to multiplex multiple streams. A part of our team was responsible for productionizing HTTP/3 (QUIC) at Uber for all mobile applications. Based on our experience, we believe that head-of-line blocking at the transport layer is more profound over wide area networks, especially mobile networks, and less of a problem within more confined private networks.

S3 vs GCS: A Battle of Protocols- HTTP1.1 vs HTTP2

S3 has stuck with the HTTP/1.1 protocol while GCS uses the HTTP2 protocol for object transfers between client and the storage buckets. This decision does have significant performance consequences due to several enhancements made in the HTTP/2 spec. Moreover, the HTTP/1.1 clients used by S3 do not fully support all the enhancements defined in the HTTP/1.1 specification. Together these factors can lead to significantly higher delays for S3 access, directly impacting compute costs.

Benchmark Comparison

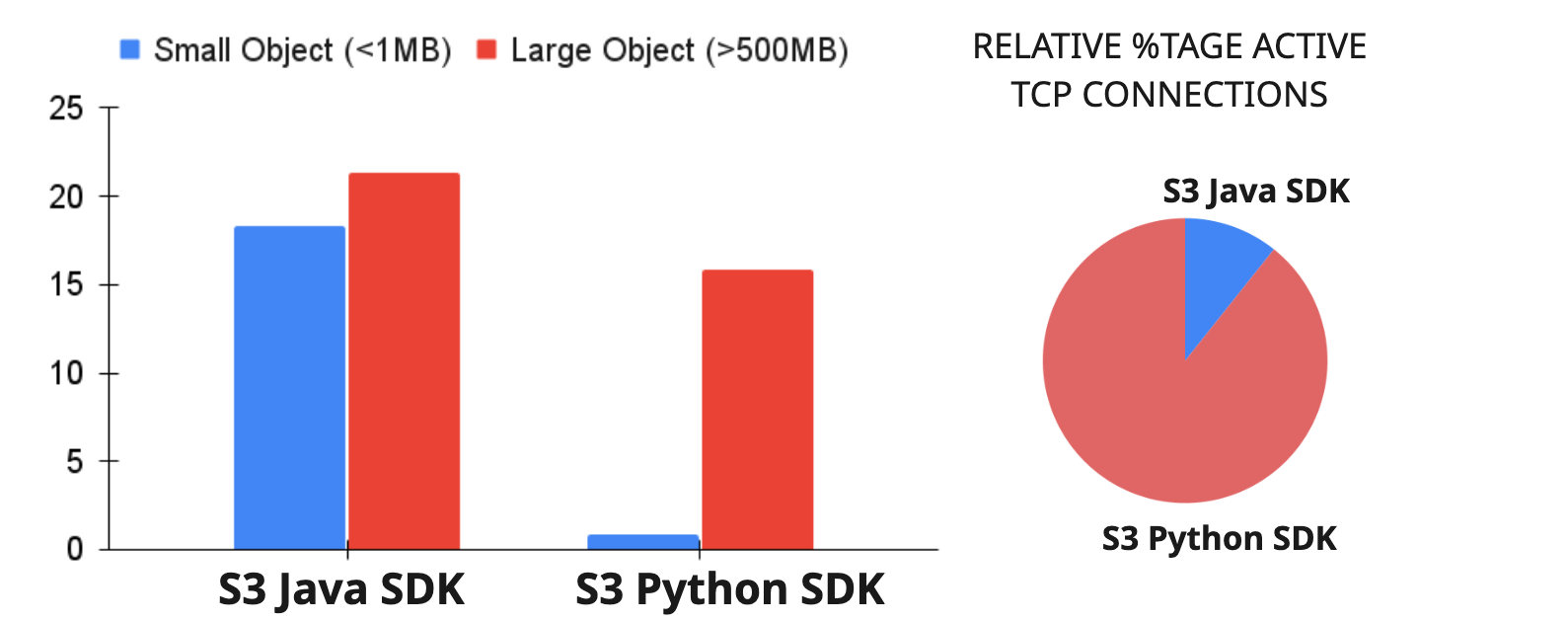

We analyzed the data from one of our production environments in AWS, where we run lakehouse ingestion workloads over m8g.12xlarge instances with 48 cores. We witnessed high latencies in the order of 10’s of secs even for objects that were <1MB in size. The access patterns were such that we saw multiple requests being made for a mix of small objects (<1MB) and a few large data files (500MB-1GB). We implemented a micro-benchmark to quantify the performance differences between S3 and GCS using this same access pattern from production data. We used async clients to ensure that the requests are not bottlenecked at the application layer.

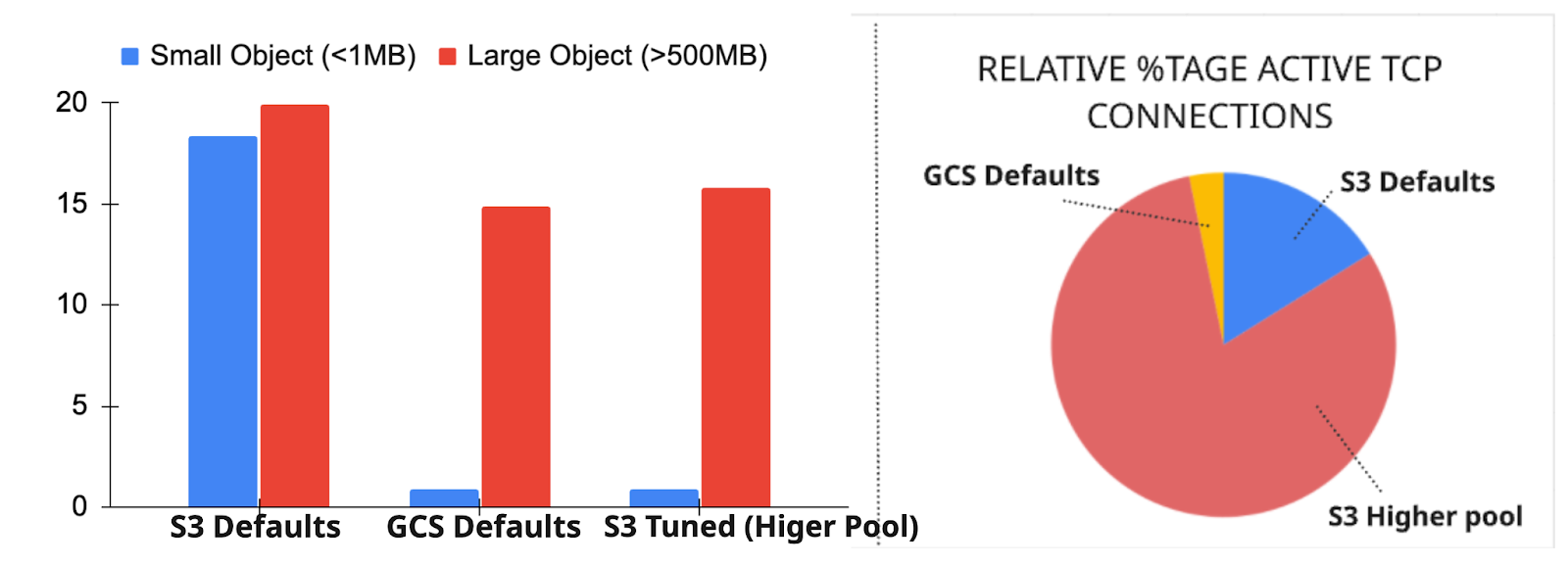

The benchmark results are shown in the figure below. With S3 java client (SDK v2) configured with defaults, we were able to reproduce the issue and the median latencies for small objects was extremely high (> 15secs). We attribute this to the HTTP head of line block issue that we spoke about earlier - the requests for the smaller objects are waiting for the larger objects to complete due to unavailability of connections in the pool. Even with default configurations, we saw that the median and p99 latencies for small objects in GCS was below 1 second.

While we were able to circumvent the issue using higher value for connection pool size for S3 clients, as shown in the right figure, it meant a significantly higher number of TCP connections being created over time than the GCS case. TCP connection setup and maintenance of TCP state can definitely be a significant overhead [1,2,3] for the infrastructure, including the compute instances themselves. Even if we ignore the impact of the TCP connection overheads, it still puts the onus on the user to properly configure the appropriate pool limits based on workload patterns and other factors (e.g., number of cores).

In the following sections, we dive into the SDK and HTTP implementations to further explain the implication of HTTP performance differences between S3 and GCS, like the one illustrated above.

HTTP/1.1 performance might depend on specific implementations

AWS provides SDKs for different languages, including java, javascript and C++. While the SDKs intend to abstract out the underlying HTTP layer from the developers, it’s important to ensure that the HTTP optimizations are being used. For instance, AWS SDK v2 for javascript had not enabled the persistent connections (HTTP Keep-Alive) by default . In benchmarks, enabling persistent connections helped reduce the latencies by ~60%. Note that the benchmarks were done for DynamoDB, but the impact should have been similar for S3.

Similar issues have been raised with Java SDK for certain HTTP clients, where the default values for idle timeouts are too conservative (5 secs) and it’s not possible for developers to configure them. Setting lower idle timeouts may not effectively reuse TCP connections as the connections are terminated if they are idle for longer than the configured timeout value.

In fact in our benchmarks on S3 using the java and python SDKs, we saw differences in how the connection pool is implemented. As shown in the figure below, for the same values for max connections, when using python SDK, we did not see the head of line blocking, resulting in low latencies for the smaller objects. After digging, we found that boto3, the library used for Python SDK, creates a new TCP connection even if the pool limit is reached. Instead of adding that connection to the pool, it's closed right away. As a result, we saw significantly (8-10X) more TCP connections created with the Python SDK.

Another aspect to keep in mind is that the AWS SDKs generally allow developers to select from a few HTTP implementations. For instance, AWS Java SDK has more than a couple of options, including the AwsCrtHttpClient that is a performant HTTP client implemented by AWS. While this is great for flexibility, it also puts the onus on the developers to ensure they validate that the HTTP implementations use the correct configurations. This is especially true for HTTP/1.1, since its performance could be on par with HTTP/1.0 if optimizations such as persistent connections are not taking effect.

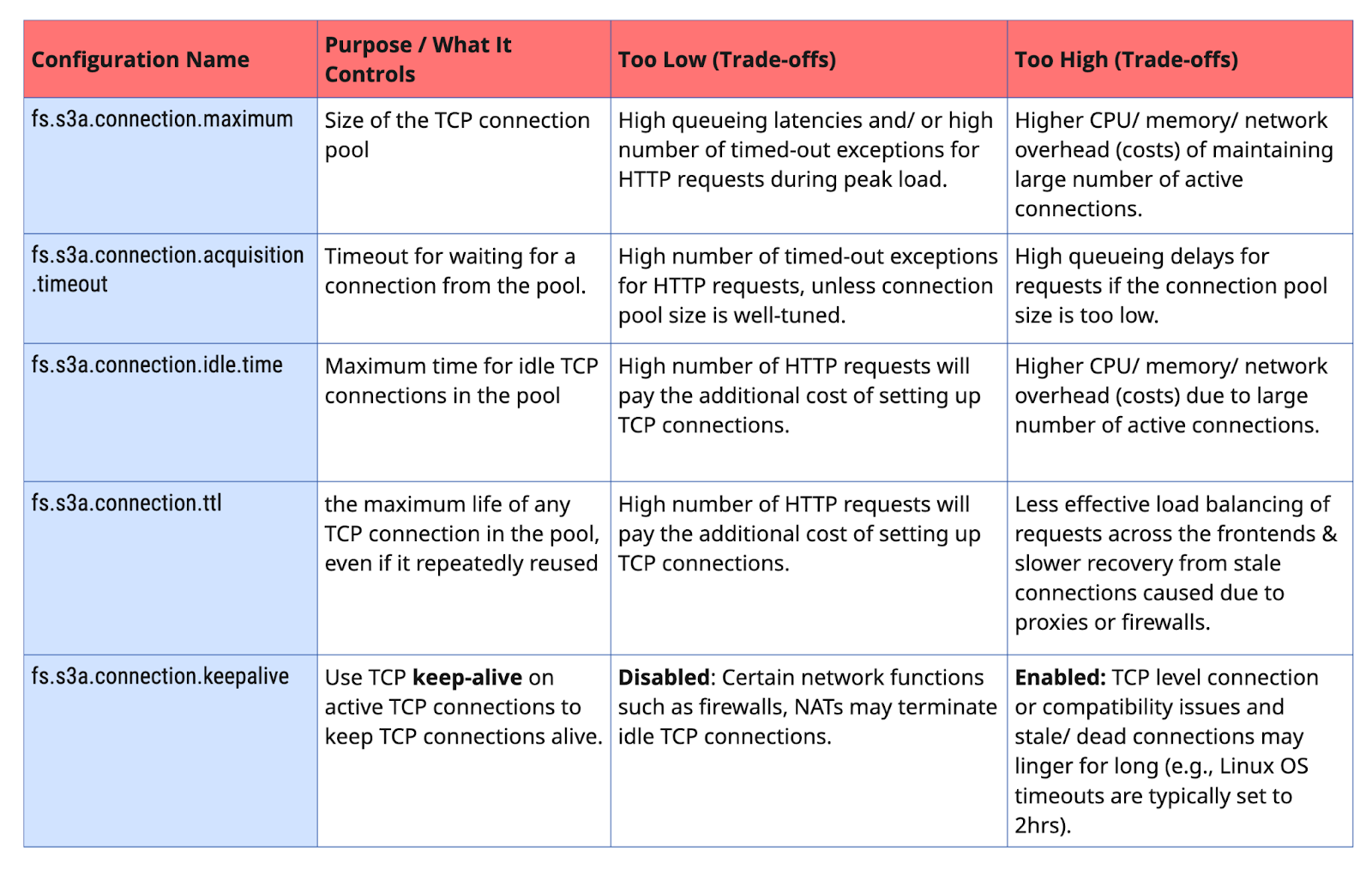

Most data lake implementations such as Apache Hudi and Apache Iceberg use the hadoop-aws or hadoop-gcs libraries. These libraries provide a file system abstraction over Object storage. Although they use the AWS and GCP SDKs for requests to the storage systems, it adds another layer of complexity for the users to ensure the HTTP is used in a performant manner. For instance, hadoop-aws overrides the defaults for the maximum number of connections, idle timeout and acquisition timeout and disables TCP Keep-Alive.

HTTP/1.1 pipelining has poor adoption

Ideally with HTTP/1.1, clients making requests to S3 should be able to multiplex concurrent requests over a shared TCP connection. However, in practice HTTP/1.1 pipelining has a very poor adoption. Popular browsers such as Chrome and Mozilla have disabled pipelining by default. One of the most popular edge and service proxy projects, Envoy does not have full support for pipelining. To the best of our knowledge, AWS S3 does not explicitly mention full support for pipelining either. ApacheHTTPClient is the default HTTP client used by the AWS Java SDK, and they call out the complexity of implementing pipelining and compatibility issues with servers.

The main reasons for the poor adoption are the complex implementations that had led to a lot of issues, mainly from the server, proxies and other network intermediaries. HTTP and TCP connections often traverse several network middle-boxes, such as firewalls, proxies etc. In certain cases transparent proxies split the end-to-end path into two separate sessions: one between the client and the proxy, and another between the proxy and the server. For pipelining to work effectively, all these middle-boxes need to implement it correctly.

The other concerns include head-of-line blocking and the early and quick adoption of HTTP/2. In fact there was an official IETF memo to improve adoption of HTTP/1.1 pipelining and address such limitations that were slowing adoption.

S3 client implementations use connection pooling

Although the exact reasons why S3 does not officially support pipelining are unclear, it is evident from client behavior that pipelining is not employed. Instead, S3 client implementations rely heavily on connection pooling to support concurrent requests. Typically, clients maintain a fixed pool of TCP connections (configurable with a default of 50). Each incoming request is either assigned to an idle connection from the pool or, if the limit has not been reached, a new connection is created.

In contrast, GCS clients do not need a connection pool (although it can still be used for higher concurrency, fault tolerance etc.). With HTTP/2 support, multiple concurrent requests can be sent over a single TCP connection, eliminating the need for the static pool approach used by S3. This difference is illustrated in the figure above.

Concurrency of requests using connection pooling is constrained by the pool’s maximum connection limit. We need a cap on the maximum connections because each TCP connection adds overhead (for maintaining state) across the process, operating system, and network. Under peak load—or when concurrency spikes – available connections may run out, causing requests to queue or fail with timeouts. Retried requests often worsen the issue until the load drops.

The real cost isn’t just queued or failed requests—it’s the wasted compute time spent waiting on connection setup, queueing, or timeouts. This idle compute time directly drives up costs. On the contrary, the better scenario is to maximize concurrency by issuing multiple parallel requests to keep compute resources busy. As this technical blog puts it: “Making an S3 GET call is 27.5x cheaper than waiting 1 second on AWS EC2!”

Optimizing performance in HTTP/1.1 is challenging

Modern data lake workloads can easily stress the connection pool. With Vectorized IO adding multiple GET requests per thread, prefetching, file rewrites and merges etc. larger pools are even more important. In typical deployments, we have seen values of 1000s for the maximum size of the connection pools. The hadoop-aws library sets the default max connections to 500, up from the 50 default set by AWS SDK.

When managing diverse workloads and pipelines in the lake, tuning the configurations for hadoop-aws can be challenging. The configurations to manage the HTTP/1.1 connection pooling for S3 can be especially difficult but also important for performance (or costs). To get a sense, we listed a few key configs for hadoop-aws with details about the trade-offs when selecting values that might be too conservative or too aggressive.

Of course, there are several other configurations, such as HTTP request and connection timeouts, block size for uploads (POST) etc. that needs to be tuned for both HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2. However, we believe that those are general HTTP configurations that most developers understand and can be configured to values that may work across a wide range of workloads and environments. However, the above mentioned configurations are specific to the use of connection pools, and the importance of which are specific to HTTP/1.1.

Our Approach

At Onehouse, we strive to continuously innovate and optimize the vertical stack across data processing engine, compute and network infra to help our customers get the best possible performance to cost ratio. The main challenge for us is that we cannot rely on tuning configurations based on workload, or environment. We are building a lakehouse platform, and we won’t be able to scale the platform effectively.

As a first step, we have gotten the foundations right - standardized our HTTP client implementations for S3, and set appropriate configuration parameters that should work generally for the expected range of workloads. While AWS Cloudfront—a CDN service for S3 that supports HTTP/2—can be used, it is generally optimized for serving static and dynamic web content such as images, videos, and other assets. In the context of data lake deployments, CloudFront often adds unnecessary complexity and cost. This is because the compute infrastructure (EC2, EKS, or EMR) resides in the same AWS region as the S3 bucket, allowing data access to occur over the private AWS backbone network.

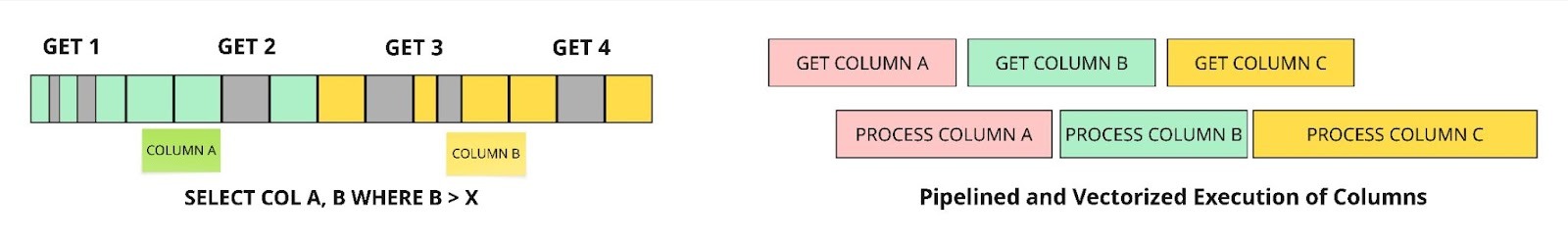

Besides that, our approach is to build more intelligence on the application layer to overcome the inefficiencies of the HTTP layer. Most notable are concurrent GET calls for byte ranges, coalescing requests for non-contiguous byte ranges, pipelined execution and vectorized columnar processing as shown in the figure below. While these are well-known techniques, they have to be carefully designed based on two key characteristics of cloud- there is a bandwidth limit on a compute node (for e.g., up to 15Gbps for m8g.4xlarge instance type in AWS) and the billing for S3 or GCS is based purely on the number of requests (assuming the bucket is in the same region as compute). In the case of S3 specifically, we also have to consider all the trade-offs that we discussed in the previous section - for instance triggering several concurrent requests that can cause higher queueing delays or the need to configure a much larger TCP connection pool size.

Conclusion

The migration of data lakes to object storage platforms has shifted performance considerations from distributed file system semantics to the intricacies of HTTP-based access. The choice of protocol versions—HTTP/1.1 versus HTTP/2 —plays a central role. HTTP/2’s multiplexing and header compression avoids head-of-line blocking, reduces connection overhead and increases utilization of network bandwidth.

By sticking with HTTP/1.1, the performance of S3 access is left to the choice of SDK and HTTP client implementations and how well the configs are tuned for the workload. It also depends on how well the application is implemented to negate some of the inefficiencies of HTTP/1.1. On the other hand, by adopting HTTP/2 quickly, GCS access is a lot more performant out of the box. Using access patterns from real production workload, we demonstrated 15X higher latencies for S3 against GCS.

While we hope S3 adopts HTTP/2 in the near future, in the case of large-scale analytical workloads, these protocol differences can translate into real cost savings, lower tail latencies, and more predictable throughput. At Onehouse, we incorporate these insights into how we architect our platform—optimizing connection management, evaluating protocol behavior under realistic workloads, and balancing the tradeoffs between portability and provider-specific tuning.

If you are running a data lake, or are considering to bootstrap a data lake in the cloud, take Onehouse’s managed ingestion, SQL or Spark jobs products for a test drive. With these—and many more—optimizations built into the platform, you can start saving money today!

Read More:

Subscribe to the Blog

Be the first to read new posts